Our research spans four frameworks of economics and international trade

With virtually every product embodying some level of value added across borders, it is vital to rethink our traditional understanding of imports and exports

Innovation thrives when firms collaborate within networks of related industries, making cluster dynamics key to understanding regional competitiveness

Understanding the dynamics of interconnected economic regions helps explain patterns of diversification, economic growth and distribution of wealth

We enhance the traditional gravity model, long used to quantify factors affecting bilateral trade, by incorporating machine learning and transport time

We use these complementary frameworks to dynamically analyze the St. Lawrence – Great Lakes region’s economy with our digital twin.

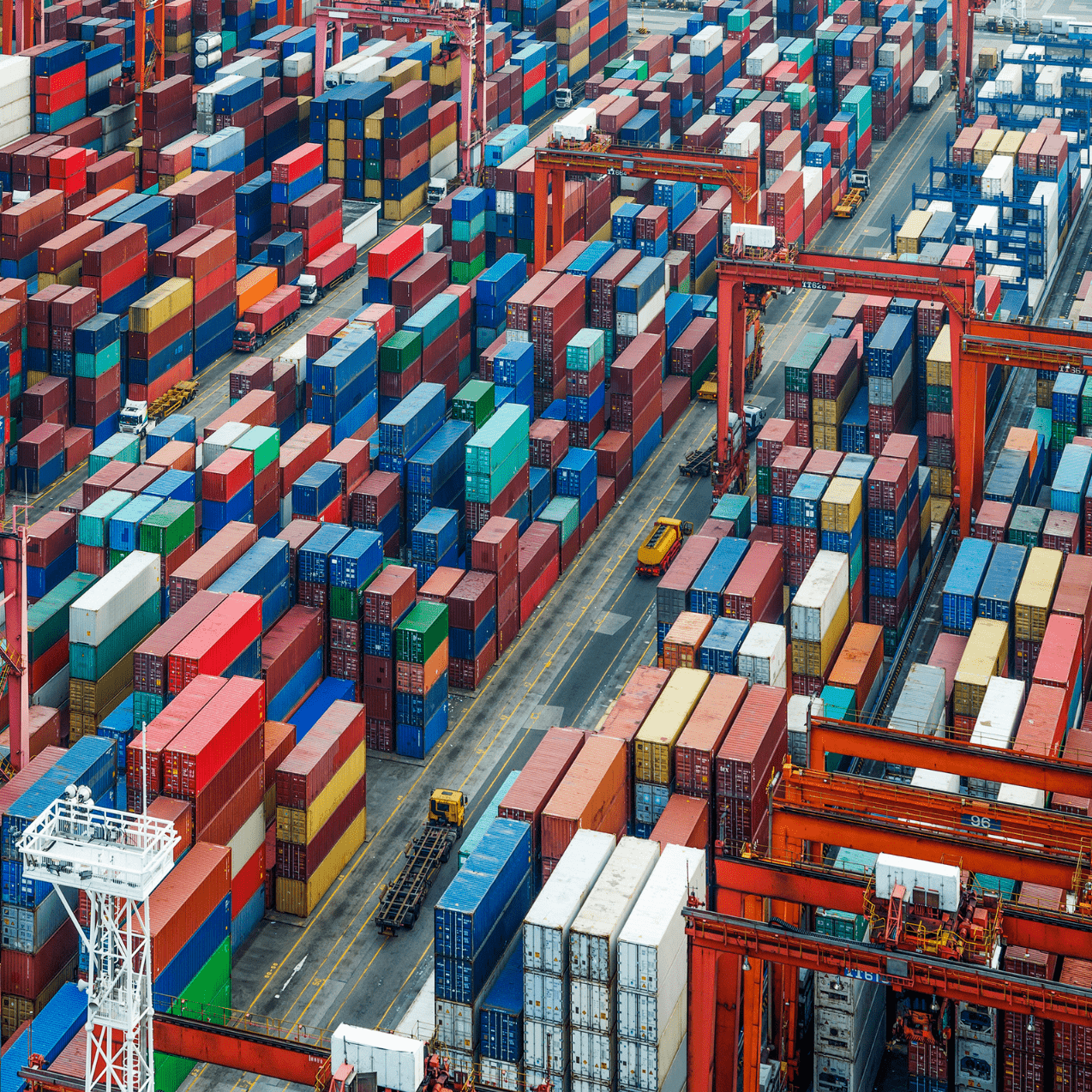

Global Value Chains

The decentralized cross-border fragmentation of a company’s value chain is a powerful source of efficiency and competitiveness. Companies have structured and outsourced their internal processes around these Global Value Chains (GVCs) to pursue comparative advantages of locations, despite of the increased complexity in managing operations and susceptibility to shocks in the global economy. GVCs increasingly account for the growth in international trade, global GDP and employment. This makes it an interesting dimension for the study of a region’s economy.

The GVC framework allows to study the organization of global industries through the analysis of the structure and the dynamicsof complex interactions between actors involved in a given supply chain. The measurement of value in a supply chain lies in the sequential value added by each actor in the form of inputs, from a product’s conception to its consumption. Mapping this input-output structure shows not only the flow of tangible and intangible goods and services but also shows the true value of an economy’s output.

Industrial Clusters

Clusters are a geographic concentration of companies, specialized suppliers, service providers, firms in related industries and associated institutions that are linked together through cooperation and competition within a particular industry. These linkages ease the movement of knowledge, technology and talent, leading to spillovers that form the foundations for local collaboration. In fact, an industry’s ability to produce complex and high-value products becomes contingent on the presence of strong interrelated clusters.

Clusters offer a key opportunity to peruse the relationship between competitiveness, productivity and prosperity. Globalization has resulted in an uneven distribution of economic activity and consequently economic performance and competitiveness across regions. Policymakers have increasingly turned their focus towards clusters as a tool to manage a rapidly changing economic landscape on a sub-national level. Therefore, any effort of crafting cluster policy requires a comprehensive understanding of economic activity within a region.

Economic Complexity

The modern economy of a country is a myriad of complex internationally interconnected economic systems. These systems have variance in the nature of its economic activity that can be traced down to the difficulty in transferring and combining different pieces of explicit knowledge that people hold. Highly complex products require coordination between hundreds of people leveraging their expertise to create individual components of the product.

Economic complexity is a powerful quantitative tool that heavily relies on big data and machine learning models to explain differences in diversification patterns, economic growth and income inequality. Metrics of complexity provide key estimates about the overall potential of an economy, by measuring the combined presence of economic factors by being agnostic about what those factors may be. It allows to introduce relevant heterogeneity between industries and products by summarizing the vectors that best explain the geography of thousands of economic activities.

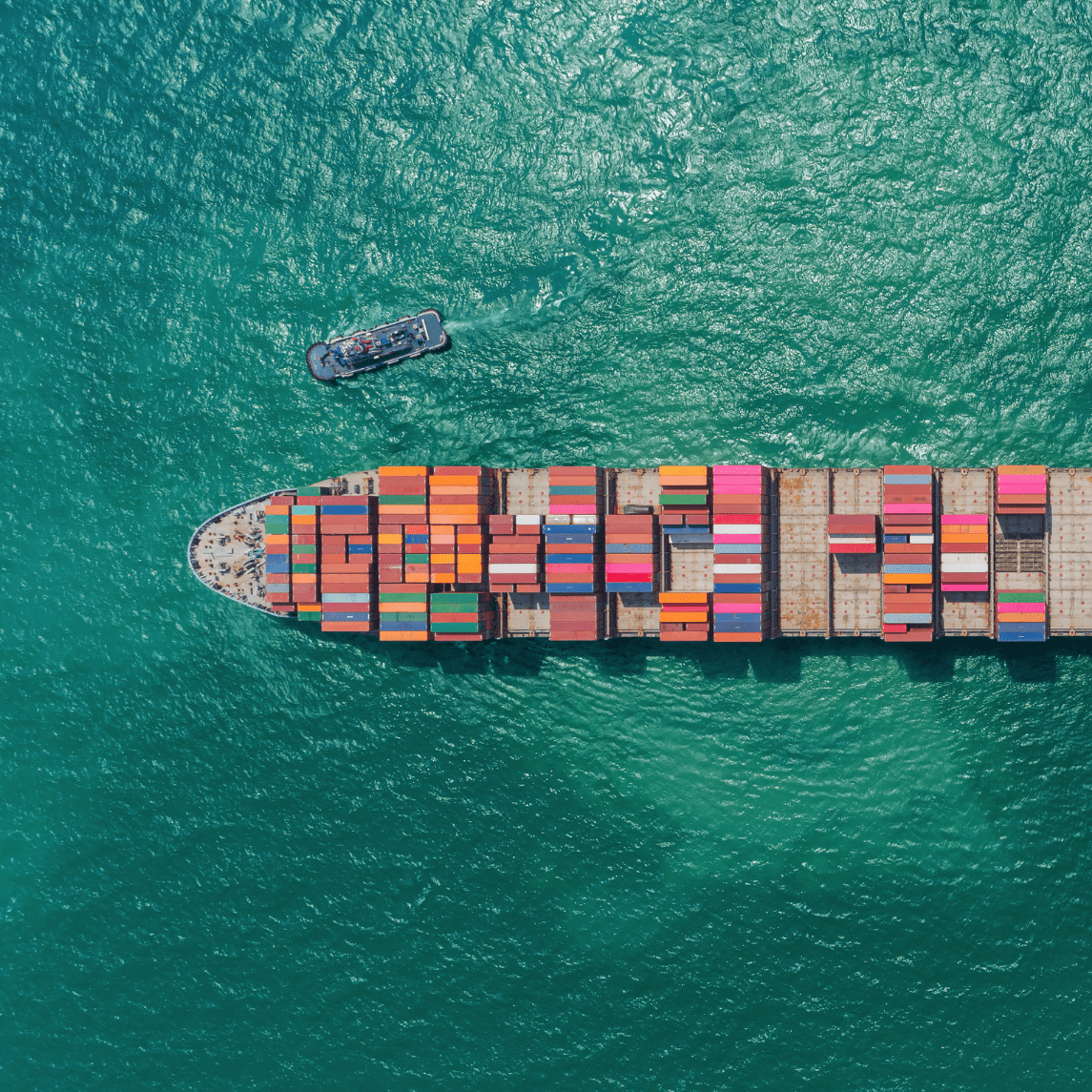

Gravity Model

The gravity model has long been used in international business literature to explain the effect of various distances between a pair of countries. The traditional gravity model posits that bilateral trade between two countries is proportional to their economic size (in terms of GDP) and inversely proportional to the geographic distance between them. However, subsequent variations of the model have looked at distance beyond its geographic denotation. The model can be augmented with proxies for geographic distance, leading to a more sophisticated and complex understanding of distance.

Between the two systems of trade and transportation, geographic distance is a common variable that plays a crucial role. Within this context, distance can mean transportation modes, intermodal transportation capacities, supply chain cybersecurity, supply chain decarbonization and so on. The proliferation of digital data has allowed access to information such as the actual distances between two ports. Data science can be used to accurately determine the actual distance travelled by a container ship when transporting goods between two countries.